THE MYSTERY

An ACES’ CSI (Control Systems Investigator) was called to the scene of an overheating side-seam drum welder. This is a primary machine for this customer, a barrel manufacturer. Its job is to take a flat piece of metal, roll it into a hoop and weld it down the side. Unfortunately the drum welder was a ‘60s- era vintage so replacement parts were unavailable.

THE CLUES

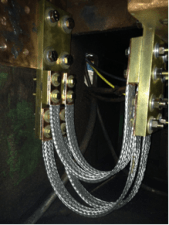

The CSI began by inspecting the conductors that carried current from a stationary bus bar to a moving bus bar, both water-cooled. The moving bus bar attached to the lower press wheel and had a vertical motion of about 3”-6”. The conductors on this end also showed recent signs of being extremely hot, while the conductors on the stationary end were still bright, clean and shiny under the cover plate.

THE PERP

The conductor/bus bar assembly was clearly not capable of carrying the amount of current demanded of it. The operator explained that the moving bus bar had recently broken and a new one had been installed.

THE SOLUTION

Since there were no resources for replacing the bus bars, the CSI removed them, along with the cover plates and conductors, and took them back to ACES’ fabrication shop to see about designing new ones.

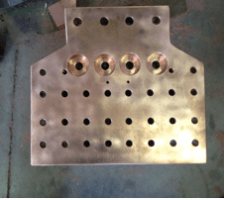

The drum welder typically runs at around 400 amps. The CSI, along with other ACES staff, engineered a solution that would carry up to 3200 amps and included eight cables on two different levels, two bus bar connectors milled by tapping 12 holes in a copper plate, and two step blocks containing 4 holes each. The CSI transported the new parts back to the factory and installed them in the drum welder.

Upon powering up the welding machine and running barrel stock through it, the CSI observed that the temperature was rising about 20 degrees per barrel and that the top conductors were much hotter than the bottom ones.

MORE INPUT NEEDED

A call to the manufacturer to gain insight as to why the top conductors were hotter clarified the situation: All conductors needed to be on the same level on the bus bar connectors.

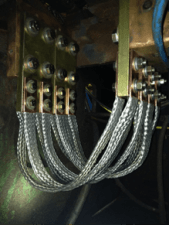

The CSI removed the parts once more, brought them back to the shop and cut the bottom sections off of the bus bars. He re-assembled the conductors using a back-to-front and criss-cross pattern to ensure that they were all delivering current at the same proximity to the bus bar, eliminating any imbalance. This new design also removed the step blocks.

The operator ran barrel stock through once again. Now all the cables were running very close to the same temperature, but still getting hotter at about 20 degrees per barrel.

When the temperature reached 320 degrees and smoke was rising from the conductors — which were jumping wildly toward the center of the machine with each weld — the CSI stopped the operator.

At this point the CSI knew that the current passing through the conductors had to be much greater than 400 amps — or even 3200 amps for that matter.

The CSI measured the current through one of the eight cables and observed a reading of 1500 amps, which — assuming all eight cables were carrying an equal amount of current — added up to 12,000 amps total.

BACK TO THE DRAWING BOARD

The CSI went back to the shop to engineer a solution involving enough conductors to carry more than 14,000 amps.

THE FINAL SOLUTION

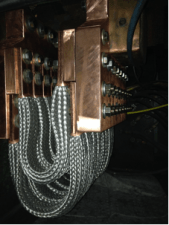

This new design involved 16 cables rated at 900 amps each, which connected to two 3’ x 4’ copper bus bars, each one 2” thick, carrying a 38-hole pattern and supporting an 18-hole step block.

After much drilling, machining and tapping of holes, countersinking of bolt holes and polishing of contact surfaces, the new design was ready to test. An anti-oxidation coating provided the finishing touch.

The operator powered up the welder for the third time and ran several barrels through as the CSI monitored the temperature. The temp of the conductors all stayed below 130 degrees. The welds on the barrels appeared to have good penetration and uniformity. The CSI allowed the operator to continue with production and this temperature was maintained under sustained running.

The next day the operator commented that the welder was performing better than it had in a long time. Now this machine should have many more years of useful service, turning out perfect cylinders to be finished into barrels and drums.

Faced with equipment 50 years old, but still mostly serviceable, ACES was able to engineer and machine new parts to keep this welder in commission, saving the owner downtime, upheaval and the considerable cash outlay of installing a new machine.

Troubleshooting, maintaining and repairing vintage equipment are just a few of our specialties. To rejuvenate a classic piece of machinery and keep it in production, give us a call for a free estimate.